|

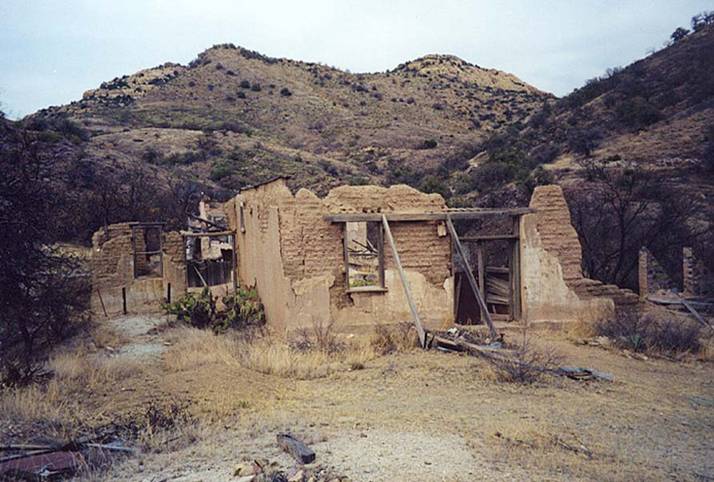

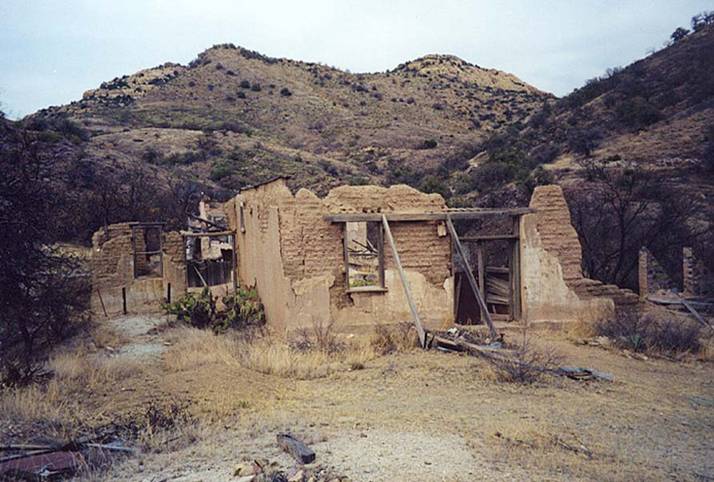

Ruby Mercantile

|

|

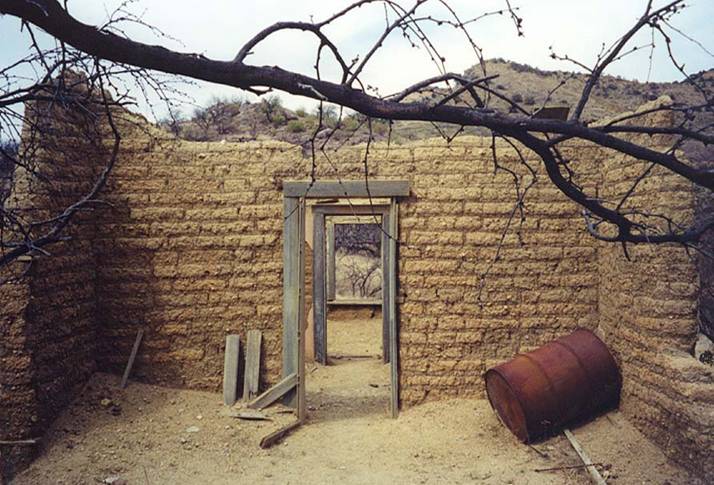

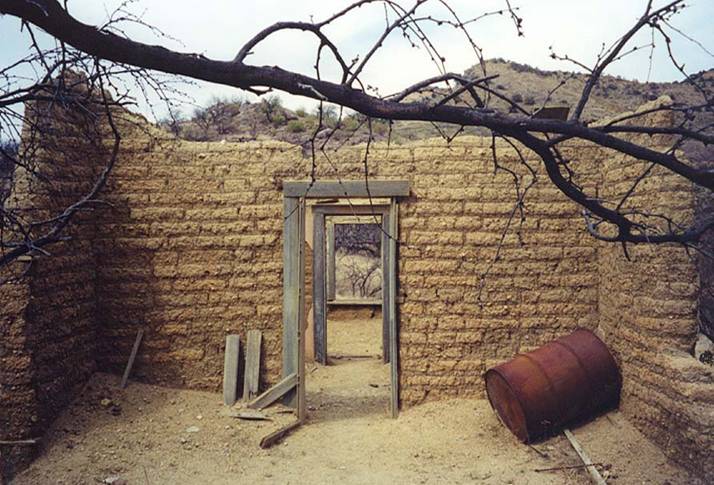

Pfrimmer House |

Column No. 44

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

Today the population of the Oro Blanco area is sparse. Long ago miners cleared

the live oak forests to supply timber for mine buildings and tunnels, and fuel

for steam engines to run the processing mills. Mesquite trees have replaced the

lush, tall grasslands. Most of the current residents of the Oro Blanco Mining

District live in shacks or trailers, having chosen a life away from

civilization.

Unfortunately, this now open country, so near the international border with

Mexico, has become a primary U.S. entry corridor for illegal aliens and drugs.

The roads that served the miners so well are still unpaved and under maintained.

The alien and drug problems, along with the poor road conditions, discourage

visitors to the area.

Only about a dozen buildings remain in the Ruby ghost town, and they are

deteriorating rapidly. Ruby Road used to come right into the camp from Arivaca

and then, south of the school, turned sharply north towards Nogales. Today, the

road cuts across the northern boundary of Ruby. The gate at the entrance to Ruby

is open during daylight hours.

Ruins of the major mining buildings still look out over the valley below. The

warehouse is still in pretty good shape. The galvanized roof of the old mill

building provides a shelter for Ruby’s caretakers.

Long forgotten is the constant ear-splitting noise of the milling machinery that

once processed 400 tons of ore per day. Remnants of the assay office are still

standing. Lingering hauntingly is the ghost of chief chemist Fred Gregory who

committed suicide there with a mixture of sulfuric acid and cyanide after

finding his wife cheating on him.

The dam built in the late 1890s by George Cheyney to form Ruby Lake is still

there, doing its job, though over the years the dam regularly endured damaging

floods. In the past, the scene of both wonderful recreation and tragic drownings,

the Lake today is stocked with bass, catfish, and bluegill.

The tailings pond, the fine-grain, sand-like remains of milling the ore from the

mine, still covers a huge area. It looks uncannily like a white sandy beach. The

rousing cry to “Play Ball!” can be heard in the whispers of the wind over the

old baseball field.

Only the walls of the mercantile and post office, the scene of the infamous Ruby

murders, still stand. The ghosts of brothers John and Alexander Fraser, and

Frank and Myrtle Pearson may be heard rustling among the ruins.

The schoolhouse remains a whole structure. Books, pieces of furniture, and an

old oil stove can be found inside. The teeter-totter board and the large slide

are still there, outside the school. So many fond memories reside here. It’s

difficult to believe now that 160 children studied here in the late 1930s.

The combined doctor’s office and hospital building is still recognizable. It

seems as if the ghost of beloved Dr. Julius Woodard is still there treating

patients. The two bunkhouses remain in fair shape. The smell of those satisfying

meals for single miners can be imagined.

The concrete jail appears ready for use today. The outside wooden door is

covered with metal. The inside door is made entirely of steel, hand forged by

Ruby blacksmith, Manny Gutierrez in the 1930s.

The Ruby general manager’s house, the mine superintendent’s house - the home of

hippie squatters in the 1970s, and the school may be the buildings in the best

shape. Owners Pat and Howard Frederick have “fixed up” the general managers

house a little and reside there when staying in Ruby.

Columnist Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon’s old house is rapidly deteriorating. Only a

few adobe walls remain to remind her of her years in Ruby. Perhaps saddest of

all, there are piles of lumber, piping, and wire sitting in front of the old

bunkhouses. Trucks delivered the material just a few years ago, when dreams of

preserving or renovating Ruby were blooming. But these modern building supplies

remain unused, except for occasional roof repairs and for picnic tables,

apparently left to the same fate as Ruby.

The public can see the ghost Ruby town, either privately, or on regularly

scheduled tours offered through Pima Community College. Private visitors should

contact Pat or Howard Frederick to arrange the visit and to coordinate with the

onsite caretaker’s schedule. As of Spring 2005, permits are $12 per day per

person for hiking, wildlife viewing, and exploring. Visitors can also fish in

one of Ruby’s two lakes, stocked with bass and blue gills, for $18 per day or

$30 for the weekend. The lakes are private, so a state fishing license is not

required. The owners permit camping on the property but not hunting. Howard

Frederick says, “We treat it as a primitive area. What you bring in, we ask that

you take out. Also, because some of the plant life is rare, we ask that you

bring your own firewood. … Because of the way the mine was dug there are some

hazardous spots that need to be avoided and that the risk of land collapsing in

these areas should be respected.”

Visitors can get to Ruby by automobile from two directions on Ruby Road. The

first approach is through Arivaca, approaching from the north. About six miles

south of Arivaca on the Ruby Road (Forest Road 39), at the Santa Cruz County

line, the paved road turns to dirt and remains so for the six additional miles

to Ruby. The terrain is relatively flat and the Forest Service periodically

grades the roadbed so the road does not require a high clearance or 4WD vehicle.

The second approach to Ruby is from the southeast on AZ 289, which starts a few

miles north of Nogales, off Interstate 19. AZ 289 is paved for about 10 miles,

before becoming a dirt road (Forest Road 39) for the remaining 14 miles to Ruby.

This dirt road twists and turns through the Atascosa Mountains and offers a

spectacular view of the Oro Blanco country. Though longer and somewhat more

primitive than the approach from Arivaca, this road also does not require a high

clearance or 4WD vehicle.

Pima Community College sponsors public tours of Ruby. The usual schedule is one

or two tours per month, from October through May. The tour takes all day, from

the 8:15 am departure from Pima Community College in Tucson to the return around

5:30 pm. Pickups/drop-offs in Green Valley can be arranged. Cost is $69 per

person (Spring 2005). For arrangements, contact the Registration Office at Pima

Community College at 520-206-6468.

Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon has led these public tours since October 1994. She drives

the 12-passenger van and provides a historical perspective on Ruby from her

years living there as a child in the 1930s. Cahoon says of her nostalgic tour

guide experience, “At first the emotion was painful because of the memories

that were there and to see the houses deteriorating. … but it became easier,

until now you can’t keep me away. The memories become sharper each time. You see

a spot or something and you know something happened there. Then the memory comes

back. Every little bit of history, and your life there you find, is a gold

mine.”

(Sources: Sam Negri, “Ruby in the Rough,” Tucson Monthly, February 1998; Julia

Bishop, “Ruby: A Ghost of Arizona History, Arizonian, July 1998; “Remembering

Ruby” website)

|

Ruby Mercantile

|

|

Pfrimmer House |